I recently went on a Persian Wars tour of Greece. The tour was based on the fifth century BC Persian invasion of Greece and the itinerary mostly covered the major battle sites. In the hope of being able to better enjoy the tour (and to use this excuse to finally get back to dedicated reading of classical literature), I started reading Herodotus’ Histories. I started with the aim of finishing the whole thing before my tour. Then, settled for the more modest aim of reading the chapters that were associated with the Persian Wars.

While reading book 4 chapter 9, I came across this story about the origins of the Scythians. (Holland, 2015).

“When Heracles awoke, he roamed the entire country searching for them, until at length he arrived in the land known as Hylaea. There, in a cave, he found a creature who was half-maiden and half-viper, a being two in one: upwards from the buttocks she was a woman, and below them a serpent. Heracles, after he had gawped at her in astonishment, asked her if she had seen any stray mares about. ‘Yes’, she answered, ‘I have them myself. I will give them back to you, but only after you have slept with me first.’ That being her price, Heracles duly had sex with her; but because she wanted to keep him by her side for as long as possible, while he just wanted to get hold of his horses and go, she kept putting off returning them to him. At last, however, she did give them back, saying, ‘When these mares turned up here, I kept them safe and sound for you, and now you have rewarded by for taking care of them – for I have three sons by you. Spell out for me what I should do when they reach adulthood – settle them down here in this land, of which I am the mistress, or send them off to you?’ To this question of hers, Heracles is said to have replied, ‘When you are sure that your children have reached manhood, do as I suggest, and you will not go wrong. Watch and see if any of them can string this bow, and buckle on this belt, as I am doing now. He who can, settle him down here in this land. Whoever cannot complete the tasks I have set, however, send him from the country altogether. Do this, and not only will your spirits be gladdened, but you will be carrying out my instructions as well’.”

This story immediately appeared familiar to me. I realized the story had featured in the Mahabharata – one of the two major Indian epics. The hero Arjuna goes on a mini-Odyssey after he walks in on his brother and their wife.

(I am not doing a woke ‘he/they’ here. The five brothers were indeed married to one woman, who was theirwife. They take yearly turns to spend time with her and take oaths to not interfere during each other’s turn. At one instance however, Arjuna had to break his vow to retrieve his bow from the bedroom and save a man from bandits. Consequently, he must go on exile which kickstarts his mini-Odyssey.)

The story features in his mini-Odyssey, where he encounters the daughter of the king of the Nagas (a Sanskrit word for snakes). Below is an English translation of the relevant episode (Ganguly, n.d.)

“One day that bull amongst the Pandavas, while residing in that region in the midst of those Brahmanas, descended (as usual) into the Ganges to perform his ablutions. After his ablutions had been over, and after he had offered oblations of water unto his deceased ancestors, he was about to get up from the stream to perform his sacrificial rites before the fire, when the mighty-armed hero, O king, was dragged into the bottom of the water Ulupi, the daughter of the king of the Nagas, urged by the God of desire.

And it so happened that the son of Pandu was carried into the beautiful mansion of Kauravya, the king of the Nagas. Arjuna saw there a sacrificial fire ignited for himself. Beholding that fire, Dhanajaya, the son of Kunti performed his sacrificial rites with devotion. And Agni was much gratified with Arjuna for the fearlessness with which that hero had poured libations into his manifest form. After he had thus performed his rites before the fire, the son of Kunti, beholding the daughter of the king of the Nagas, addressed her smilingly and said,

‘O handsome girl, what an act of rashness hast you done. O timid one! Whose is this beautiful region, who art you and whose daughter?’

Hearing these words of Arjuna, Ulupi answered,

‘There is a Naga of the name of Kauravya, born in the line of Airavata. I am, O prince, the daughter of that Kauravya, and my name is Ulupi. O tiger among men, beholding you descend into the stream to perform your ablutions, I was deprived of reason by the God of desire. O sinless one, I am still unmarried. Afflicted as I am by the God of desire on account of you, O you of Kuru’s race, gratify me today by giving thyself up to me.’

Arjuna replied, ‘Commanded by king Yudhishtra, O amiable one, I am undergoing the vow of Brahmacarin for twelve years. I am not free to act in any way I like. But, O ranger of the waters, I am still willing to do your pleasure (if I can). I have never spoken an untruth in my life. Tell me, therefore, O Naga maid, how I may act so that, while doing your pleasure, I may not be guilty of any untruth or breach of duty.’

Ulupi answered, ‘I know, O son of Pandu, why you wanderest over the earth, and why you have been commanded to lead the life of a Brahmacarin by the superior. Even this was the understanding to which all of you had been pledged, viz., that amongst you all owning Drupada’s daughter as your common wife, he who would from ignorance enter the room where one of you would be sitting with her, should lead the life of a Brahmacarin in the woods for twelve years. The exile of any one amongst you, therefore, is only for the sake of Draupadi. You are but observing the duty arising from that vow. Your virtue cannot sustain any diminution (by acceding to my solicitation). Then again, O you of large eyes, it is a duty to relieve the distressed. Your virtue suffers no diminution by relieving me. Oh, if (by this act), O Arjuna, your virtue does suffer a small diminution, you will acquire great merit by saving my life. Know me for your worshipper, O Partha! Therefore, yield thyself up to me! Even this, O Lord, is the opinion of the wise (viz., that one should accept a woman that woos). If you do not act in this way, know that I will destroy myself. O you of mighty arms, earn great merit by saving my life. I seek your shelter, O best of men! You protectest always, O son of Kunti, the afflicted and the masterless. I seek your protection, weeping in sorrow. I woo you, being filled with desire. Therefore, do what is agreeable to me. It behooves you to gratify my wish by yielding yourself up to me.’

Vaisampayana said, ‘Thus addressed by the daughter of the king of the Nagas, the son of Kunti did everything she desired, making virtue his motive. The mighty Arjuna, spending the night in the mansion of the Naga rose with the sun in the morning. Accompanied by Ulupi he came back from the palace of Kauravya to the region where the Ganges enters the plains. The chaste Ulupi, taking her leave there, returned to her own abode.’”

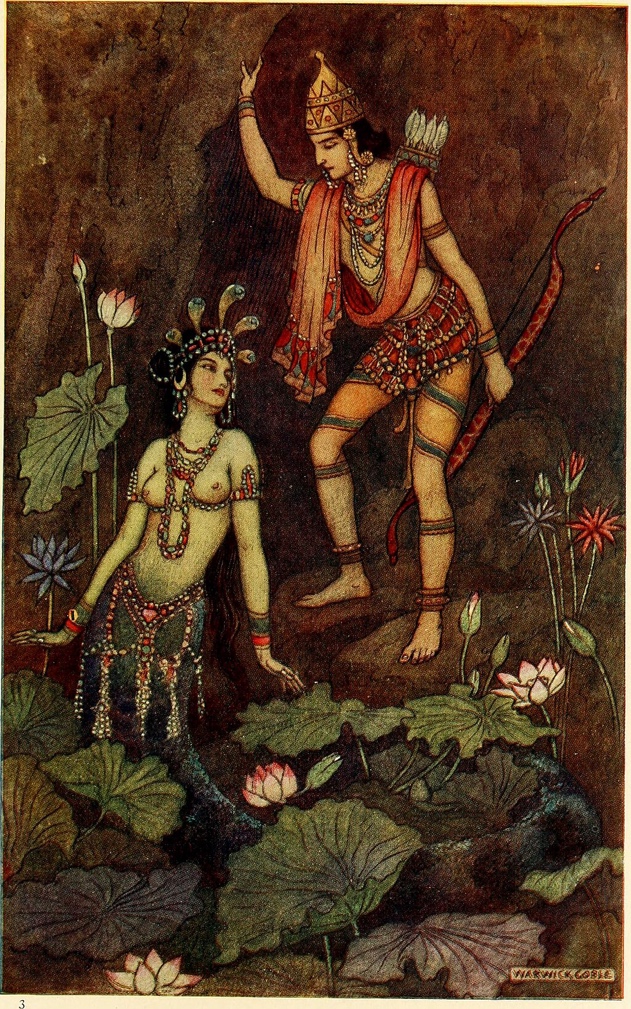

In several versions of the story, the Queen Ulupi is also described as half woman and half snake (of course, the top half was woman).

(Wikimedia Commons, n.d.)

But it was not just this similarity that intrigued me. The story of his encounter with the queen is also considered to be the origin story of my community. I belong to a community called ‘Nair’, who are based in the south-west of India. Like the Scythians, the Nairs are also a matrilineal and matriarchal community. Although, Victorian ‘progressiveness’ facilitated by British colonialism significantly dented their matriarchal credentials. These were then further enervated by modernization and by the community’s integration with the rest of the Indian republic.

Despite this, some customs did linger on. Until my mother’s generation, women never changed their surnames after marriage. Kids took on their mothers’ surnames.

Traditional Nair family units consisted of women, their siblings and the women’s children (as against the man, his wife and his children). Generational wealth transferred through women and their daughters. Marriage itself was not a binding event that formed new familial bonds but was rather a transitory arrangement that could be called off by the woman whenever she pleased (again like the Scythians) (Holland, The Histories Herodotus, 2015).

There are several theories regarding the origin of this system. One theory is that this is how most human societies had functioned during pre-agricultural times and that the Nair community was one of the few where it lingered on.

Another theory considers the Nairs’ social function. They were a warrior caste and were always out and about killing each other over the pettiest blood feuds. When all the men were always mindlessly chopping each other up, the empowered women brought communal and social stability. (Pillai M. )

Both theories must have some truth to them. But the second theory possibly discounts the autonomy and agency of the women, exemplified by the fact that there were also Nair women warriors.

All the hacking and murdering had enabled the Nairs to become the ruling elite of the region and many of the kingdoms or fiefdoms were ruled by Nair women. One of these women is known to us through the records of 17th century English and Dutch adventurers. This queen, whom they called Queen Ashure, was the ruler of a prominent local dynasty.

The one woman who shines among all the Attingal Ranis, however, is Asvathi Tirunal, better known as Umayamma Rani or Queen Ashure. When van Rheede met her in 1677 he was struck by her ‘noble and manly conduct’, describing her as an Amazon who was ‘feared and respected by everyone’. (Pillai)

The European observers were particularly gobsmacked by the queen’s political and sexual autonomy.

John Henry Grose records that ‘whom and as many as she pleases to the honour of her bed’ could be taken by the Rani as lovers, adding, ‘The handsomest young men about the country generally compose her seraglio’. In addition to this, James Welsh would note that the Rani could ‘change them whenever she is tired of one by sending him away and selecting another.’ (Pillai)

Yet again, strong and independent women who ruled kingdoms are called Amazons by astonished adventurers from the west, just like the Scythian women were regarded by equally astonished adventurers from the Greek world.

Let me recollect the similarities we have seen so far. A community is recorded as being founded by a half-snake half-woman queen, who woos a wandering adventurer. The people of the community follow a matrilineal and matriarchal tradition. Both communities’ women are empowered politically and sexually. Matrimonial union is not binding, and both of their women were described as Amazons by aghast western wanderers.

These are all probably coincidences. Moreover, the ancient Greek world traded significantly with the west coast of India. They may have traded their stories along with stones and spices. Yet, why did both origin stories describe the women as half-snakes? What is it that makes strong and independent women seem serpentine? Is it just good old patriarchy, where the concept itself stings like a snakebite to men who are unfamiliar with it? Maybe the lack of control over wily women fills the patriarchal man’s mind with treachery, fear, awe and wonder — feelings redolent of serpents.

My wife’s ancestral deity is a serpent God, and she does inspire awe and wonder in me. It is heartening to know that, through all these years, somethings about strong and independent serpent women never change.

Works Cited

(n.d.). Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Arjuna_and_the_River_Nymph_by_1913.jpg

Ganguly, K. (n.d.). Section CCXVI. Retrieved from Wisdom Library: https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/the-mahabharata-mohan/d/doc4289.html

Holland, T. (2015). The Histories Herodotus. In T. Holland, The Histories Herodotus (p. 266). Penguin Classics.

Holland, T. (2015). The Histories Herodotus. In T. Holland, The Histories Herodotus (pp. 302-304). Penguin Classics.

Pillai, M. S. (n.d.). The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore. In M. Pillai, The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore (pp. 90-91).

Pillai, M. (n.d.). The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore (Kindle Edition). In M. Pillai, The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore (Kindle Edition) (pp. 270-271).

Leave a comment